By Natalie Peirce

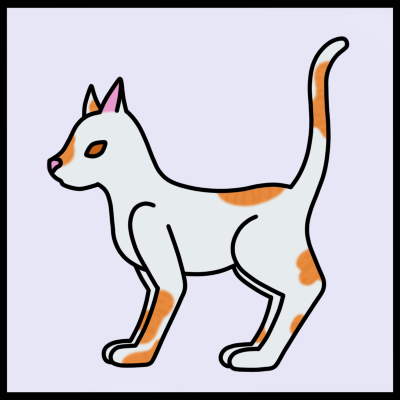

I was fortunate enough to grow up with cats, and there was one litter in particular that caught my interest growing up. One of my mum’s colleagues bred cats in free time. His female, while in heat, snuck out of the house just once and ended up having an ‘oops litter’. This litter consisted of 3 kittens.

The first kitten, a male, was ginger and white with amber eyes and was adopted by my grandma at 8 weeks old. The other 2 kitten were female, and the breeder kept them for himself – intending to breed them at some point in the future. Unfortunately, circumstances changed and he couldn’t keep them anymore. My mum ended up adopting the pair at 18 months old – a cat who was tortoiseshell and white with green eyes, and a cat with seal pointing and blue eyes.

Naturally, I couldn’t help but wonder just how these 3 cats, born in the very same litter, could be so different from each other. I knew that there was possibility that there were multiple fathers to the litter, but theoretically it could have just been the one! We will never really know, but it did spark a lingering curiosity as to how it all works and what their father(s) may have looked like.

Black colour:

The black colour in cat fur is caused by the pigment eumelanin, and one of the main enzymes involved with this pigment’s production is known as TYRP1. The gene that codes for TYRP1 has a few different alleles – one of which is dominant, and two of which are recessive.

The dominant allele, B, causes the production of black eumelanin, resulting in black fur. The recessive alleles, b and bl, cause the eumelanin produced to be a different colour. The allele b results in the production of a dark brown eumelanin, and the allele bl results in the production of a lighter, reddish-brown eumelanin. These variations are known as ‘Chocolate’ and ‘Cinnamon’, respectively.

As the allele B is dominant, a cat only needs one copy of it in order to have black fur (B/B, B/b, B/bl). The allele b is recessive to B but dominant to bl, meaning that a cat will only need one copy of it to have chocolate coloured fur, but only if the B allele is not present (b/b, b/bl). The allele bl is recessive to B and b, meaning that a cat needs two copies of it in order to have cinnamon coloured fur (bl/bl).

Orange colour:

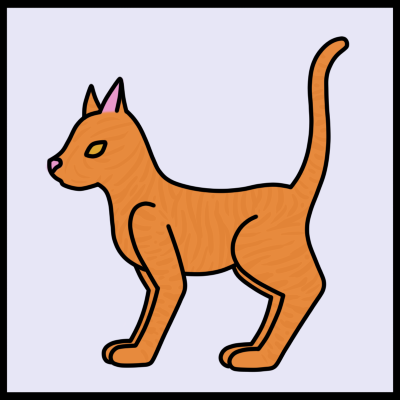

The orange colour in cat fur is caused by the pigment phaeomelanin. The gene responsible for the production of this pigment, Arhgap36, is sex-linked and is found on the X-chromosome. This trait is dominant, meaning that only one copy of the dominant allele, O,is needed to produce phaeomelanin. This pigment then completely replaces the eumelanin in that specific cell.

As this gene is on the X-chromosome, the majority of male (XY) cats will only have one copy of the gene, either O or o, and will be orange or not orange (black) as a result. Female (XX) cats, however, have two copies of the gene. O/O will result in in an orange cat, o/o will result in a black cat, and O/o will result in a tortoiseshell cat – a cat that has a mix of orange and black fur. In some rare cases, a male cat can also be tortoiseshell due to having two X-chromosomes (XXY) and a copy of each orange colour allele (O/o). This is why this trait can also referred to as ‘Sex-link red’.

Interestingly, and unlike black fur, orange fur will always have some kind of tabby pattern to it, regardless as to whether the cat is agouti or not. It will also override other tabby patterns.

White colour:

The KIT gene determines whether a cat will have any white in its coat or not, provided that the cat does not have albinism. This gene has many different alleles, resulting in a large variation of the amount of white in a cat’s fur and how it is distributed throughout their coat.

Epistatic white:

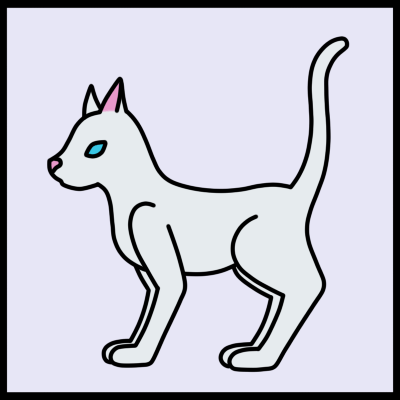

This is also known as ‘Dominant white’ and is caused by the dominant allele, WD, of the KIT gene. A cat only needs one copy of this allele to have a completely white coat. This is because this allele interferes with the replication of melanin-producing cells in skin (melanocytes) and therefore prevents the production of both eumelanin and phaeomelanin (the black and orange colours). The wild type allele, w, is recessive does not interfere with melanin production, resulting in a non-white cat. As this allele modifies the expression of two other genes, it is described as being epistatic.

This allele is often linked to two other traits – blue eyes and congenital deafness. While it is a common myth that all white cats with blue eyes are deaf, it is true they are a lot more likely to be deaf when compared to other cats – with white cats with two blues having a 65-85% chance of being deaf!

White spotting:

White spotting is where a cat’s coat is a mix of white and one or two other colours. The allele for this, ws, is found on the KIT gene, and is recessive to the epistatic white allele (WD) and dominant to the wild type, non-white allele (w). Provided that the epistatic white allele is not present, a cat only needs one copy of this allele in order to have white spotting.

The white spotting allele causes white patches of fur by disrupting the migration of melanoblasts, the precursors to melanin-producing cells, in the skin during a cat’s development. This means that these areas of skin will not produce any black or orange pigment and the fur is left white.

There has been a lot of debate on exactly how white spotting works in cats. It was initially thought to be a completely separate gene to epistatic white, instead of being a different allele on the same gene. It was also thought that if a cat had two copies of the allele for white spotting that more of their coat would be white (50-100%) when compared to a cat with only one copy of it (0-50%). This idea has put into question by a 2022 study (Górska et al.), however, as it was shown that cats possessing only one white spotting allele can have a coat that is more 50% white in colour.

Salmiak:

This is the most recently identified KIT allele, having been identified by Anderson et al. in 2024. From what we can tell, this appears to be a very recent mutation, having first been spotted in a single cat population in Finland in 2007. The fur of a salmiak cat resembles that of salty liquorice, aka salmiak, and consists of a coloured head with a white stripe down the face, white neck, white paws, white tail tip, and white speckling throughout the body and limbs.

The salmiak allele, wsal, is recessive to all other KIT alleles. We know this as, in the same 2024 study where it was first identified, non-salmiak cats have been found possessing only one copy of the salmiak allele.

Birman gloving:

Birman gloving, wg, is where only a cat’s paws are white. This allele is primarily found in Birman cats, being one of the identifying features of the breed, and is recessive to the other KIT alleles (WD, ws, and w). However, at this point in time, we don’t how this allele interacts with the salmiak allele.

Albinism:

Unlike other causes of white fur, albinism is not caused by an allele on the KIT gene; it is instead associated with the TYR gene. This gene is associated with colour pointing in cats (which we’ll cover in more detail in a later section). There are two alleles for albinism, c and c2, and they are both recessive. While this produces a completely white cat much like the epistatic white allele does, there are a couple of key differences – cats with albinism will always have either pink or light blue eyes and they do not have an increased chance of deafness like epistatic white cats do.

Dilution:

Dilution is where the colour of a cat’s fur appears paler. This is caused by an allele on the MLPH gene, a gene which determines how much pigment gets deposited in each bit of fur. The recessive allele, d, causes the pigment of a cat’s fur to be less densely packed than the dominant allele, D, causing its paler appearance.

A diluted cat’s colour will depend on the base colour of its fur, i.e. the pigment present in the fur. Fur with a black base colour becomes blue (grey), chocolate becomes lilac, cinnamon becomes fawn, and orange becomes cream. White fur is not affected by dilution, as there is no pigment present in the first place.

Other colour variations:

Amber:

This particular colouration is found primarily in Norwegian forest cats, and is caused by a recessive allele, e, on the MC1R gene. In a cat that possesses two of these alleles, any black pigment in the cat’s fur gets changed into an amber colour. Kittens with this trait start off relatively dark and lighten as they age. The presence of the dominant allele, E, will cause the cat to have black fur instead of amber.

Russet:

This colouration is found in Burmese cats, and is also caused by a recessive allele, er, on the MC1R gene. Like amber cats, these have an orange or reddish colouration and lighten as the age.

Fever coat:

This is also known as a ‘Stress coat’ and does not have a genetic basis, but rather an environmental one. It is a phenomenon seen in some kittens, where they are born with a lighter than expected coat that darkens to the expected colour as they age. This lighter fur can be caused when the mother, during their pregnancy, experiences a high fever or extreme stress, but may occasionally be due certain medications. This fever coat does not affect the health of the kitten, just it’s colour temporarily.

Silver:

In cats with silver fur, the melanin inhibitor gene (I/i) supresses melanin production. It affects phaeomelanin more than eumelanin, resulting in a cat with silver fur. The allele for this trait, I, is dominant. However, sometimes this gene in poorly expressed and results in cats with a yellowish, rusty-looking coat. This is dubbed as ‘Tarnishing silver’.

Pointing:

Pointing, or colourpoint, is where a cat’s feet, face, ears, and tail have darker coloured fur when compared to the rest of the body. This is due to a phenomenon known as acromelanism – where pigment development is affected by temperature. In the case of cats, this means that the pigment in the colder parts of the body (the extremities) develops as it normally would, while the pigment in the warmer parts of the body has a decreased development – causing that fur there to be lighter. Interestingly, this means that pointed kitten are born white, and that their pointing initially develops the first few months after they are born.

This pointing is caused by alleles on the TYR gene, the very same gene that is associated with albinism. The wild type allele, C, is dominant to all other alleles and produces no pointing or albinism. The alleles for albinism, c and c2, are recessive to all other alleles and produce an albino cat. There are a few different alleles responsible for pointing, and these are recessive to the wild type and dominant to the albinism alleles.

The allele cs is responsible for the pointing seen in Siamese cats, where there is a high contrast between the fur colour on the extremities when the compared to the fur on the body. The allele cb is responsible for the pointing seen in Burmese cats, where this contrast in colour is a lot lower. These two alleles are incompletely dominant, meaning that if both are present then the cat will have a blend of the two traits. If a cat has cs/cs they will have high contrast pointing, if a cat has cb/cb they will have low contrast pointing, and if a cat has cs/cb they will have medium contrast pointing. This pointing with medium contrast is found in Tonkinese cats – a cross between a Siamese and a Burmese cat.

There is one other allele on the TYR gene, that we known of, that affects a cat’s coat, and that is the mocha allele, cm. This allele is a fairly recent discovery and was found in Burmese cats – causing their fur to take on a light brown colour. We don’t know for certain how this allele interacts with other alleles on the TYR gene, but it is theorised that it is incompletely dominant with cs and cb.

Agouti:

When fur is agouti, it has bands of alternating dark and light colours. This banding is caused by the agouti gene, which affects the agouti signalling protein (ASIP). The agouti allele, A, is dominant and causes the protein to function normally. The non-agouti allele, a, is recessive and prevents the protein from working as it should, resulting in fur that is one solid colour instead of banded. Agouti fur is lighter in colour than its non-agouti counterpart.

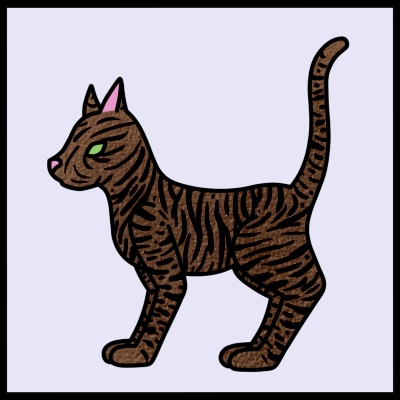

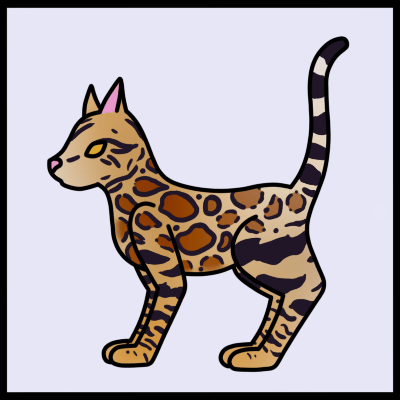

Tabbies:

In tabby cats, their fur has a patterned coat that is a mix of light and dark colours. This pattern’s background is lighter and comprised of agouti (banded) fur, and the pattern itself is made up of areas of highly pigmented fur.

Along with requiring the agouti allele to be present, there are a few more genes that can affect a cat’s fur pattern – the first of which is the Taqpep gene, also known as the tabby gene. The dominant allele for this gene, TaM, causes the cat’s pattern to consist of tight, tiger-like stripes. This is known as a ‘Mackerel’ tabby, and they usually have a signature ‘M’ shape on their forehead. The recessive allele, Tab, causes the pattern to consist of larger, less organised whorls. This is known as a ‘Classic’ or ‘Blotched’ tabby.

Another gene that affects a cat’s pattern is the ticked gene – Dkk4. The ticked gene is epistatic to the tabby gene, masking its pattern when present, and has a few different alleles. The most common of these ticked alleles are TiA and Ti+, which are incompletely dominant with each other. The TiA allele results in a coat with a sand-like appearance and little to no stripes or other patterns – this is known as a ‘Ticked’ tabby. The Ti+ allele results in a cat with a spotted coat, and this is known as a ‘Spotted’ tabby.

Other patterns:

Servaline:

The servaline pattern is similar to the spotted pattern, but has spots which are comparatively smaller and more tightly packed. This is due to a mutation on the ticked gene, Ti18V, which is paired the Ti+ allele to produce the servaline pattern (Ti18V/Ti+). The coat is primarily found in Savannah cats.

Golden:

The cause of golden fur in cats is the CORIN gene, which is a modifier of the agouti signalling protein pathway. The dominant allele, WB, does not result in a golden colour. The recessive alleles, wbSIB and wbBSH (found in Siberian and British cats respectively), cause the phaeomelanin bands on agouti fur to be wider, resulting in a golden colour.

Smoke, shaded, and tipped:

There are other factors theorised to affect the band size of agouti fur, like the CORIN gene does. This is because we have observed cats with a few other wide band traits – smoke, where the base of the fur lacks pigment, shaded, where more than half of the fur lacks pigment (from the base up), and tipped, where only the very tip of the fur has pigment. While the traits smoke, shaded, and tipped are found in silver tabbies, a variation of the shaded trait has been observed in orange fur and is referred to as cameo shaded.

Rosette:

The rosette pattern has a pale background which is covered in spots with dark outlines and centres which are shade in between the background and the outlines. This pattern is seen in wild cats, such as jaguars and ocelots, and the domesticated Bengal cat. While we don’t know exactly how this pattern works, it is suspected to be linked to the Wnt inhibitor encoded for by Dkk4, much like the ticked gene is.

Fur length:

The length of a cat’s fur is determined by the FGF5 gene, also known as the long fur gene. The dominant allele, L, results in a cat with short fur, and the recessive allele, l, results in a cat with long fur. This long fur is commonly associated with breeds such as Maine coons and Ragdolls, but can also be found in moggies. There are currently 5 known variations of the recessive allele (l), which all result to long fur.

Coat textures:

In the majority of cats, their fur is straight and short and is made up of three different kinds of hair – guard, awn, and down. Different breeds tend to have different amounts of each hair type, but all are generally present. However, there are good amount genes that can change the fur’s shape and texture.

Rexes:

The term rex refers to cat whose coat is made up of soft and curly fur. There are a few different genes that can produce a cat with rex fur; the first of which is the KRT71 gene, which is responsible for both the Devon rex and the Selkirk rex. The allele that produces a Devon rex, KRT71re, is thought to be recessive to all other alleles on this gene, whereas the allele responsible for producing the Selkirk rex, KRT71Se, is thought to be incompletely dominant with the wild type allele (KRT71+) and dominant to every other allele.

The Ural rex and the Corish rex are not due to alleles on the KRT71 gene; they are instead due to alleles found on the LIPH and LPAR6 genes, respectively. Both traits are recessive, and can be represented by LIPHur and LPAR6r (with their wild types being represented by LIPH+ and LPAR+). Additionally, the LaPerm trait is thought to be a dominant trait, although no specific locus has been identified for it.

Wirehair:

Wirehair cats have crinkled and coarse fur, somewhat similar to the fur of rexes. It is thought to be either a dominant or an incomplete dominant trait, although more research is needed before we can be sure. We are also unsure of the gene(s) associated with the production of this trait.

York chocolate:

York chocolate cats have a uniquely silky coat, as they lack the undercoat that other cats have. This trait is found on the Yuc gene and is thought to be the result of its dominant allele. As there are very few, if any, members of this breed still living today, we are unfortunately to confirm this.

Sparse fur:

A cat with a sparse coat will have thin fur that sparsely covers its body, as each of their hair follicles are further apart from each other when compared to the average cat. This is seen primarily in lykoi cats and is thought to be a recessive trait, although we don’t quite know yet which gene(s) it is associated with.

Hairlessness:

There are a couple of different genes that can cause hairlessness in cats, and they both work in slightly different ways. Firstly, you have the gene that causes hairlessness in Sphynx cats – the gene KRT71. This gene is also responsible for the curly coats of the Selkirk and Devon rexes. The allele for hairlessness, KRT71hr, is recessive to KRT71Se and KRT71+, but dominant to KRT71re.

The second hairlessness gene is the one responsible for causing hairlessness in Donskoy and Peterbald cats. The allele for this, Hp, is dominant and is potentially associated with the LPAR6 gene – the same gene responsible for the curled fur of Cornish rexes. However, more research is needed to confirm this.

Summary of proven traits:

| Trait(s) | Gene | Alleles |

| Eumelanin | TYRP1 | B > b > bl |

| Phaeomelanin | Arhgap36 | O > o |

| Epistatic white and white spotting | KIT | WD > ws > wsal, wg |

| Colourpoint and albinism | TYR | C > cb, cs, cm > c, c2 |

| Dilution | MLPH | D > d |

| Amber and russet | MC1R | E > e, er |

| Melanin inhibition | Inhibitor locus | I > i |

| Agouti | ASIP | A > a |

| Tabby | Taqpep | TaM > Tab |

| Ticked | Dkk4 | TiA, Ti+, Ti18V |

| Golden | CORIN | WB > wbSIB, wbBSH |

| Fur length | FGF5 | L > l |

| Selkirk rex, Devon rex, and hairlessness | KRT71 | KRT71Se, KRT71+ > KRT71hr > KRT71re |

| Ural rex | LIPH | LIPH+ > LIPHur |

| Cornish rex | LPAR6 | LPAR6+ > LPAR6r |

You can find all of the sources used here.