By Natalie Peirce

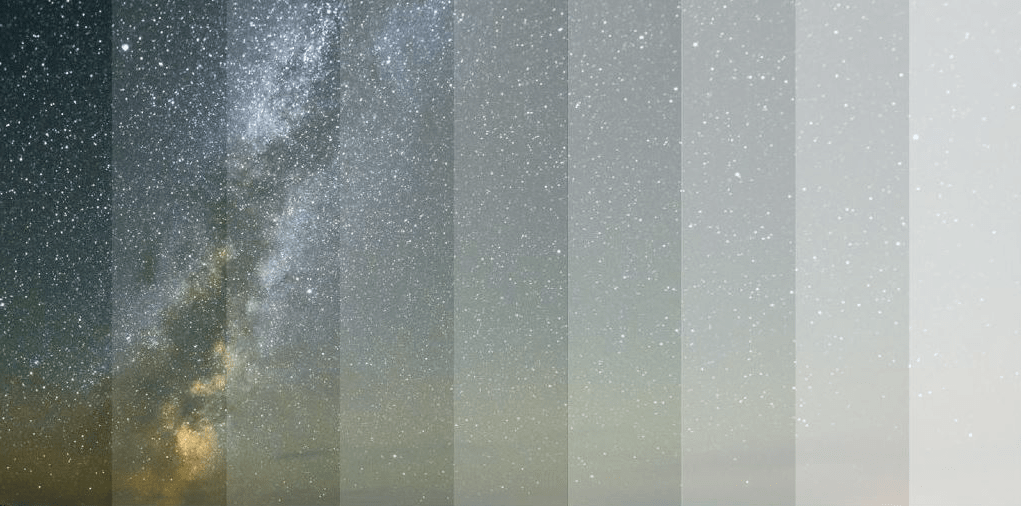

The Bortle dark-sky scale, more often referred to as the Bortle scale, was created by John E. Bortle and published in 2001. It is a quantitative scale that can be used to measure light pollution, based on what phenomena you can see in the sky and at what points they disappear. The scale ranges from 1 to 9 – with 1 being the darkest skies that the Earth has to offer, and 9 representing the sky at the near-blinding epicentres of the world’s brightest cities.

As our skies become brighter by the year, we become ever more unaccustomed to skies on the lower end of this scale and forget what the natural sky even looks like. In fact, in 1994, when an earthquake hit Los Angeles and caused the power to go out across the city, a giant, sinister, and sparkling cloud in the sky caused many to panic and call the emergency services. What they were seeing was the Milky way, unobscured by light pollution. Many people had never seen the natural sky before, and their response to its sudden appearance, I think, is quite understandable. We miss so much beauty behind lights of our own creation, and that is what I wish to highlight today.

1: Excellent, truly dark sky:

The sky is dark and awash with stars – so many, in fact, that some constellations are almost unrecognisable due to their sheer number. The Milky way, our own little part of the universe, is clear and detailed to our naked eyes. To some, it can even appear colourful, having orange or yellow-ish hues, and its centre is so comparatively bright that it casts shadows on the ground below.

A faint band of light, known as Zodiacal light, may be seen stretching across the night sky and bisecting the Milky way. A phenomenon known as airglow is visible, caused by light emitted from reactions at various heights in our atmosphere, and can change how we see the sky – potentially adding a multitude of hues including blue, green, purple, and red. You may also spot the Gegenschein, dust in the solar system largely formed by the collisions of asteroids, appearing as a somewhat bright smudge in the sky.

Many Messier objects and globular clusters are also visible. A particular object to note is Messier 33 (M33), also known as the Triangulum galaxy. It is our third largest local galaxy, following only the Andromeda galaxy (M31) and the Milky way itself, and is very visible on a night this dark. It’s also worth noting that if you spot the planets Venus or Jupiter that they are bright enough to affect your night vision, should you look at them for too long.

2: Typical, truly dark sky:

The Milky way is still clearly visible and in great detail to our naked eyes. While it is almost just as complex and structured as before, the clouds that drift in front of it may appear as dark holes in the galaxy – giving the Milky way, at times, a somewhat veiny appearance. Zodiacal light is still visible at dawn and dusk, and you may spot the colourful hues of airglow, but only near the horizon.

Looking at the sky in more detail reveals that the bright smudge of the Gegenschein is still visible, as are many of the Messier objects and globular clusters. The Triangulum galaxy, in particular, is almost just as detailed as before. On this kind of night, your surroundings may barely be visible – being only weak silhouettes against the sky.

3: Rural sky:

Although the night continues to brighten, the Milky way is still complex and strewn across the sky. It does, however, start to lose a bit of its detail near the horizon, as the clouds there are faintly illuminated. The Triangulum galaxy is now more tricky to spot, only being visible when looking at it using the very edge of your vision – a technique in astronomy known as averted vision. In contrast, the Andromeda galaxy (M31) can now be seen clearly above.

Many of the brightest globular cluster appear distinct, now that there are less of the fainter stars to clutter the sky. The Great Pegasus cluster (M15), a dense cluster of stars thought to be orbiting a black hole, and the Sagittarius cluster (M22), a bright globular cluster appearing slightly larger than the full moon, may both be easily spotted in the sky above. You may also see other objects including M4 and M5 – bright globular clusters in the Southern constellation Scorpius and the Northern constellation Serpens respectively.

Zodiacal light is still visible in Spring and Autumn, although it has started to shrink – no longer stretching across the entirety of the sky and instead reaching a good way above the horizon. We cannot see any airglow with the naked eye anymore. It’s at this point that our closest surroundings start becoming vaguely visible, and the orange hues of light pollution start to show near the horizon.

4: Rural/suburban sky:

Most of the Milky way’s finer details are now gone – only showing them off far above the horizon, although they appear dimmer than they did before. And, while the Andromeda galaxy is still nicely visible, the Triangulum galaxy is now incredibly difficult to see – even with averted vision.

The Zodiacal light, although still visible in Spring and Autumn, continues to diminish – shirking further towards the horizon and starting to become lost in its glow. The clouds are illuminated in the direction of areas with more light nearby, and the glowing sky near the horizon begins to creep that little bit higher. Our surroundings are starting to become clearer.

5: Suburban sky:

The Milky way appears washed out and dull, a ghost of itself when compared to darker skies, and it disappears completely as it approaches the horizon. Tiny hints of Zodiacal light remain, but only on the very best of Spring and Autumn nights. The Triangulum galaxy is now gone entirely, but the oval shape of the Andromeda galaxy remains visible overhead.

Some of the brighter Messier objects can still be seen clearly in the sky, such as the Orion nebula (M42), with its slight purple-ish glow, and the Beehive cluster (M44), a blurry patch of light to the naked eye. However, the clouds are now brighter than the sky, and light pollution is evident in most, if not all, directions as the glow near the horizon grows that little bit more.

6: Bright, suburban sky:

Only whispers of the Milky way remain, its faintest parts lost to sky glow. Zodiacal light is no longer visible, the Andromeda galaxy is nothing but a faint smudge in the sky, and the Orion nebula is rarely seen. As the dimmest stars and Messier objects continue to disappear from the sky, the brightest constellations become more discernible. The clouds are fairly bright now, and the light pollution above the horizon has started to turn a grey-ish white colour. Your surroundings easily visible.

7: Suburban/urban sky:

The Milky way is almost invisible, even on the clearest of nights. The Andromeda galaxy and the Beehive cluster are difficult to see, while some constellations and only the very brightest Messier objects remain recognisable. At this point, the clouds are brightly lit, and the entire sky has turned grey.

8: City sky:

The Milky way is gone. While some dimmer constellations are still visible, they lack many of their key stars. Pleiades (M45), the brightest Messier object, is visible in sky alongside few other objects, such as Ptolemy’s cluster (M7), which is located far to the South. The Andromeda galaxy and the Beehive cluster are barely visible, even on the best of nights.

The sky is a mix of light grey and orange, and is so bright that you can easily read underneath it. It is so bright, in fact, that even telescopes struggle to view the brightest objects in the sky, as most are hidden by its glow.

9: Inner city sky:

The sky is brilliantly lit. Pleiades is the only visible Messier object. The brightest constellations can still be seen, but even they are missing stars now. The only other elements we can see in the sky are the moon, the planets, and the most well-lit satellites. Everything else is gone, lost behind the light of the night.

While it’s unfortunate that we are slowly losing the night, it is far from the only thing that we lose to light pollution. The rhythms of nature itself get disrupted. In humans and other mammals, the increased light at night supresses melatonin, affecting our sleep, hormones, and immune systems. Songbirds such as robins and blackbirds start singing earlier in the season, tricked by an artificial spring, increasing the likelihood of attracting mates and predators alike. In noctuid moths, the females struggle to identify their host plants in these brighter conditions, the plants that they need to survive, and over many years have evolved to have smaller eyes in an effort to compensate. It even affects plants such as ryegrass, as night lighting can act as a depressor – limiting their photosynthesis and overall growth.

Luckily, we starting to realise our mistakes and are making efforts to preserve the natural darkness. Places such as the Aenos national park in Greece and the Eryri national park in Wales have been certified as dark sky places, which aim to preserve the natural night sky, maintain and protect local ecosystems, and educate people about responsible lighting and the importance and fragility of a dark sky. We are also starting to make efforts to reduce light pollution in more populated areas by using lights with covers, so they are directed only at specific areas, and limiting the amount of blue light that we use – using warmer coloured lights instead.

Despite our increased awareness and efforts, we are not going to stop lighting up the night any time soon. We associate light with progress and safety, and we are not willing to let go of those things quite yet. However, the future is starting to look a little less bright. And, in this case, that’s a good thing. Perhaps, in another fifty or a hundred years, we all may get to see the glittering majesty of the night sky in all its ancient glory.

You can find a list of links to all of the sources used here.

All images used were modifications of an image by Astrophotography lens.